The Demographic Transition Explained: Stages, Examples, and Implications

In Plain English

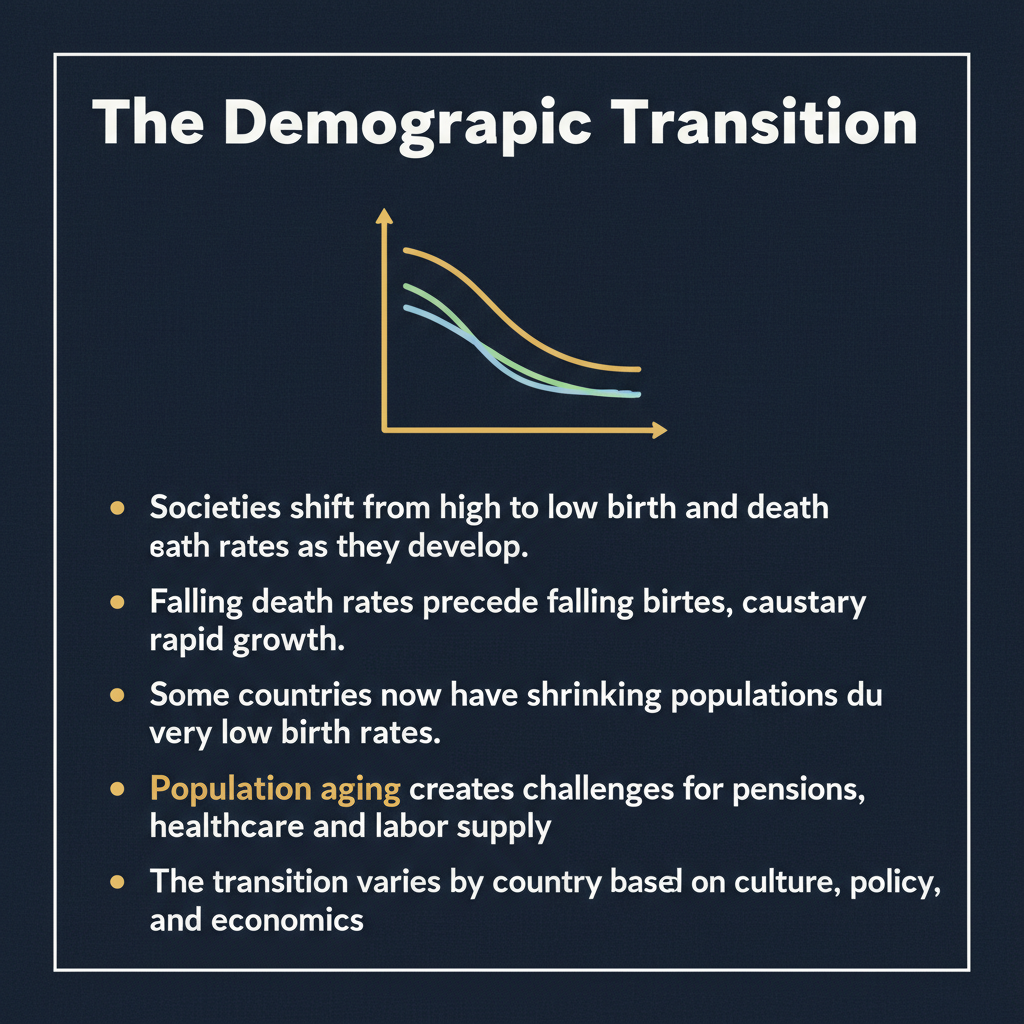

This article explains how countries change from having high birth and death rates to low ones as they develop. The research suggests that this transition happens in stages and affects population growth, aging, and workforce size. It matters because it influences how governments plan for healthcare, pensions, and jobs over the long term. Some countries are now seeing populations shrink, which brings new challenges. These shifts help explain why different nations face very different social and economic pressures.

What Is the Demographic Transition?

The demographic transition refers to the historical shift from high birth and death rates to lower rates as a society develops economically and socially. Initially, both mortality and fertility are high, resulting in slow population growth. As public health improves and industrialization advances, death rates fall first, followed later by declining birth rates. This process creates a temporary period of rapid population growth before stabilizing at a lower level. The model helps explain population trends in industrialized nations and informs projections for developing countries.

The Four-Stage Demographic Transition Model

The original Demographic Transition Model (DTM) consists of four stages. Stage 1 features high birth and death rates, typical of pre-industrial societies. Stage 2 sees death rates drop due to better medicine and sanitation, while birth rates remain high—leading to rapid growth, as seen in much of Africa today. In Stage 3, birth rates begin to decline due to urbanization, education, and changing social norms, slowing population growth. The transition culminates in Stage 4, where both birth and death rates are low, resulting in a stable, often aging population—characteristic of most high-income countries by the late 20th century.

Stage 5: The Contested Fifth Stage of Demographic Transition

Some scholars propose a fifth stage in which birth rates fall below death rates, leading to natural population decline. This stage is observed in countries like Japan, Germany, and Italy, where fertility has remained below replacement level for decades. While not universally accepted, Stage 5 reflects a shift from managing growth to managing shrinkage—posing new challenges for labor supply, pensions, and intergenerational equity. Japan, with its shrinking working-age population and rising dependency ratio, exemplifies the societal adjustments required in this phase.

Country Examples Across the Demographic Transition

France is notable as one of the first countries to enter demographic transition, beginning in the late 18th century—earlier than its industrial peers—suggesting cultural and familial factors played a role. The United Kingdom followed a more classical path during the Industrial Revolution, entering Stage 2 in the 19th century. Today, Japan represents a clear case of Stage 5, with sustained low fertility and increasing life expectancy. These examples illustrate that while the DTM provides a useful framework, the timing and drivers of transition vary significantly based on institutional, cultural, and policy contexts.

The Second Demographic Transition: Beyond Fertility and Mortality

The 'Second Demographic Transition' (SDT) theory expands the model to include post-materialist values such as individualism, delayed marriage, and diverse family forms. Associated with highly developed societies, the SDT explains why fertility sometimes falls further even when economic stability is achieved. It accounts for trends like rising childlessness, same-sex partnerships, and cohabitation without marriage—factors not captured in the original DTM. While the SDT is particularly evident in Northern and Western Europe, its applicability elsewhere remains debated.

Criticisms and Limitations of the Demographic Transition Model

The DTM has been criticized for being overly Western-centric, assuming all countries will follow the same linear path. It largely ignores the role of migration in shaping population dynamics—critical for countries like Canada or Germany. Additionally, the model does not fully account for reversals or stagnation, such as fertility increases in some religious or policy-incentivized communities. Rapid urbanization in parts of South Asia and Africa also challenges the model’s gradual timeline. As a result, the DTM is best used as a heuristic rather than a predictive law.

Why the Demographic Transition Matters for Policymakers

Understanding the demographic transition is essential for long-term policy planning. In Stage 4 and 5 countries, aging populations strain pension and healthcare systems, requiring reforms to sustain intergenerational fairness. Declining labor forces may necessitate automation or immigration policy adjustments. Conversely, countries in Stage 2 face challenges in providing education and employment for growing youth populations. The transition thus shapes economic growth trajectories, fiscal sustainability, and social cohesion over decades—making it a central concern for institutional decision-makers.

Visual Summary

Beyond the Obvious

A less commonly recognized insight is that France began its demographic transition as early as the late 18th century—decades before industrialization or widespread public health improvements—challenging the standard economic narrative of the DTM. Historical research, including analysis of parish records and family decision-making, suggests that a gradual cultural shift toward smaller families, linked to Enlightenment ideals and property inheritance practices, drove this early fertility decline. Unlike Britain, where industrialization and urbanization catalyzed demographic change, France’s transition appears rooted in rural, agrarian society where land scarcity and the Napoleonic Code encouraged couples to limit family size. This divergence indicates that cultural and institutional factors can precede and even drive demographic change independently of economic development—a nuance often missing in textbook accounts. It raises the possibility that in today’s developing countries, social norms around family size may shift earlier than expected, particularly where education and gender equity advance rapidly, even without full industrialization.